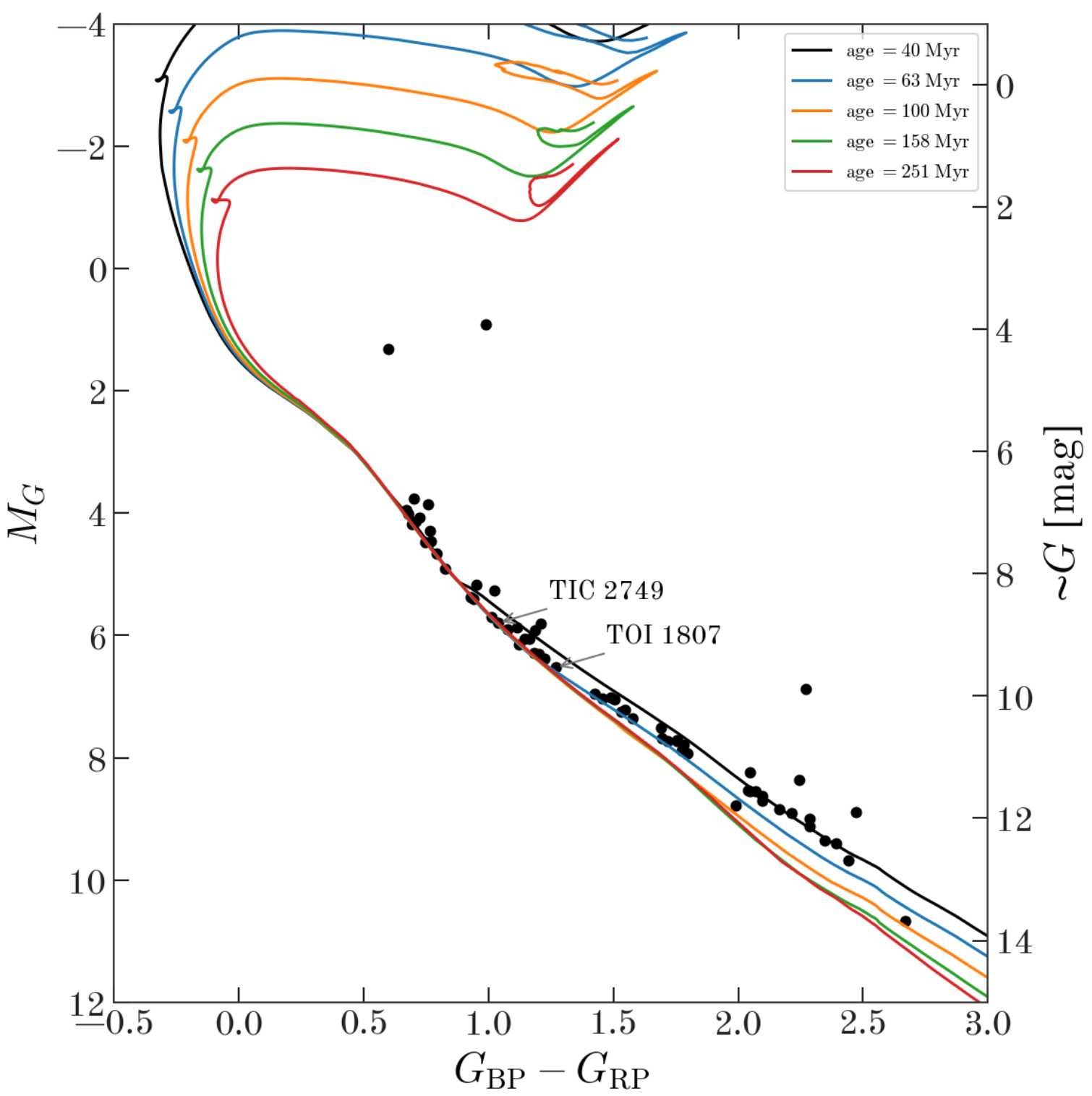

Adrian Price-Whelan and Christina Hedges started off this week’s meeting with an update about the new nearby moving group that they found when looking into the pair of transiting planet systems that they discussed three weeks ago. The header figure of this post shows a color-magnitude diagram showing the likely moving group members that they identified using Gaia radial velocities and proper motions. Christina and Adrian have compiled compelling evidence that these stars are members of a previously unknown, youngish (100 Myr), nearby (~40 pc) moving group. One feature that you might notice in the above figure is that the main sequence seems to be truncated at the bright end. Adrian and Christina hypothesize that this is caused by Gaia DR2’s bright limit for radial velocities. There was some discussion of the fact that this means that some bright (naked eye?) stars might be members of this group.

Next, David W. Hogg asked the group for feedback on a possible undergraduate project idea where the student would look at the TESS light curves for the binary systems discovered by Price-Whelan et al.. There was some discussion about what features would be expected in these light curves (eclipses, ellipsoidal variations, rotation signatures, etc.). The group had various ideas of interesting things to study, such as limb-darkening profiles as a function of effective temperature and spun up primary stars in close binaries.

Then, Ruth Angus showed some interactive figures that she made using Bokeh based on results from Lucy Lu (Columbia & AMNH) who has been developing a method to estimate stellar ages using their Galactic kinematics. The technique currently depends on binning stars in color, magnitude, and rotation period space. Ruth and Lucy have been investigating how their results depend on the choices made in this binning procedure. The group suggested that perhaps this could be recast as a huge hierarchical model where the velocity distribution (instead of the velocity dispersion) is represented as a non-parametric function of these same parameters, but this would still require choices about representation that might not be easier.

Finally, I shared a data analysis challenge that Trevor David brought to me. He is fitting astrometric observations of a binary star system with an orbital period that could be on the order of 100 years. Needless to say, the phase coverage of the observations is not great (although they do have a longer than 20 year baseline). Trevor has been using my exoplanet code and following the astrometry tutorial, but finding some painful degeneracies between parameters (especially tricky is the phase of periastron passage). There was a discussion of possible reparameterization choices, including using a series expansion of the orbit as a function of time to choose reasonable parameters. It was also suggested that we could try a rejection sampling method like the one developed by Sarah Blunt for the obitize code, but I think it will be possible to come up with a more efficient scheme in this particular case.