David W. Hogg started this week off by leading a discussion about how one might define a “discovery” in astronomy with a specific focus on the context of exoplanet detections in radial velocity surveys. This discussion was inspired by work he has been doing with Megan Bedell to make observing strategy recommendations for the Terra Hunting Experiment, an upcoming decade+ long survey to detect extrasolar Earth-analogs using extreme-precision radial velocities. One of the core questions is whether or not it is sufficient to define a detection as a precise, non-zero, measurement of the radial velocity amplitude. It might also be necessary to include a statement about the precision with which the other orbital parameters are measured. For example, a radial velocity “trend” might not qualify as a detection even if the lower limit on the amplitude is significantly non-zero. This led to discussions about whether or not marginalization is required for quantifying these detections at the limits of the survey detection threshold.

Next, Emily Cunningham shared a new project where she is using the Latte suite of Milky Way-like galaxy simulations to develop data-driven methods for understanding the assembly history of the Milky Way stellar halo. Following on earlier work by Duane Lee, Emily is working to construct a library of “template” distributions in the space of stellar abundances. These templates will be constructed by looking at accreted dwarf galaxies in the simulations and then Emily plans to model the mixed population using a linear combination of these templates to determine the relative contribution of different classes of accretion events to the assembly of the halo. After testing these methods on the simulations, Emily plans to determine which changes will be required to apply these methods to the observed stellar population even in the face of selection effects and realistic uncertainties. There was some discussion of how this methodology is similar to a low-rank matrix factorization problem and how this relationship could be used to develop a data-driven method for constructing the templates without sacrificing interpretability.

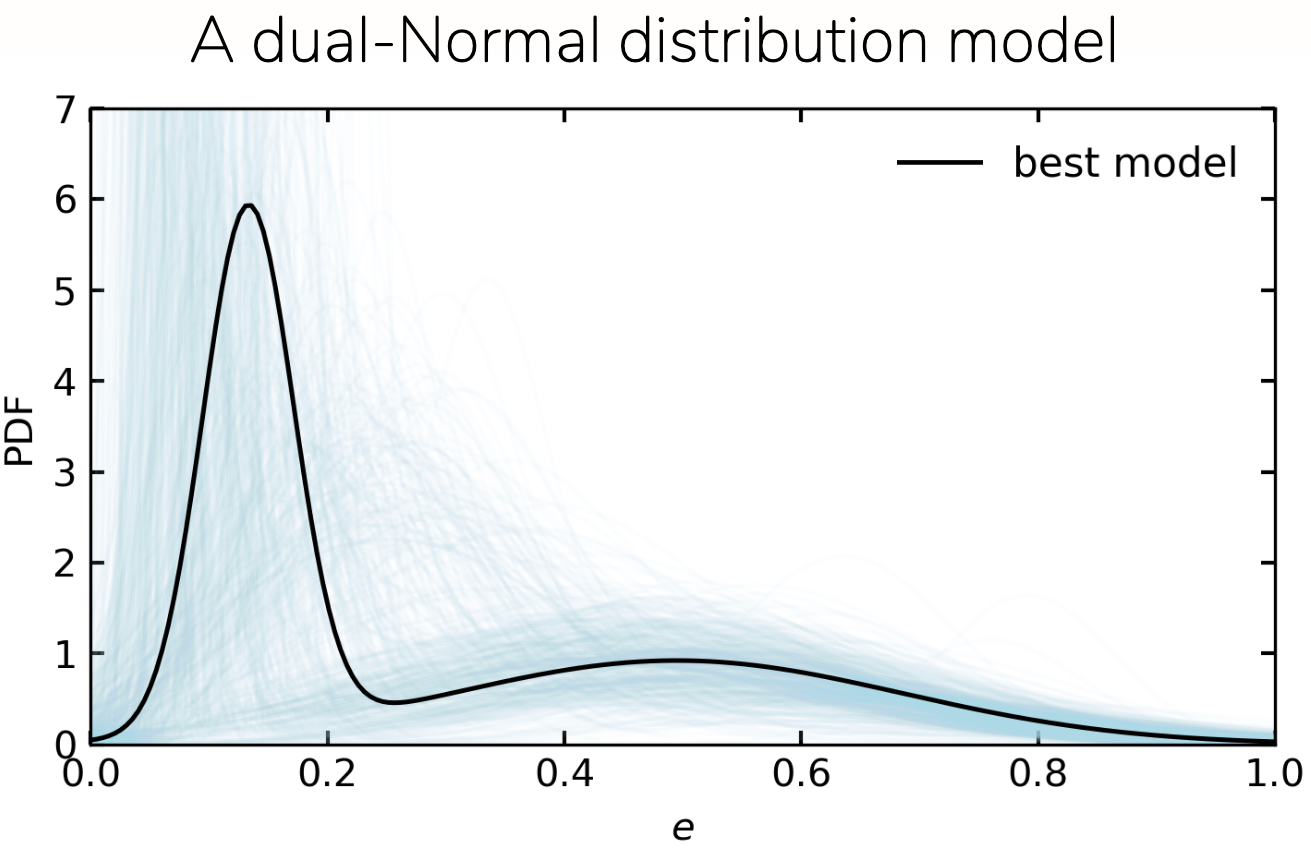

Then, Jiayin (DJ) Dong shared a project where she has measured the eccentricity distribution of warm giant planets detected using data from NASA’s TESS mission. After detecting and performing a detailed characterization of the transit light curves for a sample of about 80 warm giant planets, DJ is using “the photoeccentric effect” in a hierarchical Bayesian model to make robust inferences about the eccentricity distribution. This model is high-dimensional and the geometry of the problem can be pathological in some cases, making robust inferences tricky, but DJ has figured out these technical issues and has a working implementation in PyMC3. It is already clear that the eccentricity distribution of these exoplanets is multimodal (as seen in the header figure). The final inferences that DJ makes about this distribution will have a profound influence on our understanding of the evolution of planetary systems and she will be able to place constraints on the relative frequency of eccentric migration or in-situ formation channels.

Finally, I (Dan Foreman-Mackey) showed some plots that I have generated as part of a project in collaboration with Mariona Badenas Agusti (MIT) to revisit an interesting eclipsing binary system observed by Kepler and now TESS, using my exoplanet code. There are many technical aspects of this system that make it hard to model (there’s a lot of data and many parameters), but the physics is also non-trivial (the orbit is precessing, the stellar oscillations are coherent and measured at extremely high precision, etc.). I’m excited to get exoplanet working for this system, but I’m still struggling to get robust inferences in finite time.