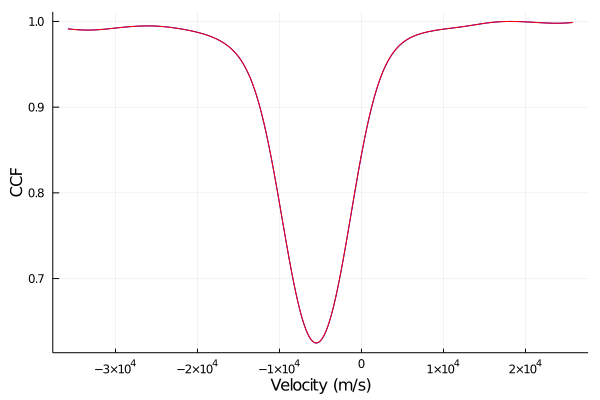

Eric Ford summarized some of his recent exploration into various approximations to the covariance of the CCF. The CCF of Echelle spectra of stars (typically with a mask that is non-zero near the location of stellar spectral lines, but sometimes a template spectrum) is frequently used as the basis for measuring radial velocities in the context of characterizing exoplanets and binary stars. The methodology goes back to the days of measuring radial velocities with photographic plates, metal plates and photocells. Of course, the advent of modern computers provides much more flexibility in what astronomers can calculate (e.g., assigning lines weights rather than simply 0 or 1 when the mask is a metal plate). Nevertheless, it appears that most exoplanet hunting teams still compute something amazing similar to the CCFs of the 20th century. (e.g., 1, 2, 3; but see 4). While these sometimes mention computing the variance of the CCF, they rarely describe computing the covariance of the CCF. Also concerning, most papers describe computing only a subset of the terms that contribute to the variance of the CCF, those that are based on the variance of the flux, but omit terms that are due the covariance of the flux at different wavelengths. If one were to use the full covariance matrix, then one can map the CCF to a likelihood function and get rigorous uncertainty estimates. But if one leaves out some terms, then the resulting velocity uncertainties will probably be overly optimistic.

Eric began thinking about this last summer, when working with Andrew Collier-Cameron and Sahar Shahaf on developing and evaluating the Self-Correlation Analysis of Line Profiles for Extracting Low-amplitude Shifts (SCALPELS) algorithm for removing apparent RV shifts due to changes in the shape of the CCF (5, Appendix B). For that paper, they had a large sample of spectra, so they chose to make use of the sample covariance of the CCFs. Actually, we replaced the sample covariance of the CCF with the sum of two terms: (1) a rank-reduced version of the sample covariance of the CCF that captures the large-scale structure of the CCF covariance, and (2) an analytical model for the near-diagonal terms that can be scaled to match the signal-to-noise of each spectrum. That seemed to work well for the HARPS-N solar dataset (6), but might not work as well for datasets with significantly fewer and/or lower signal-to-noise spectra, such as several groups are currently working on as part of the EXPRES Stellar Signals project.

Eric described a few possible approaches. The most direct solution is to simply compute the full covariance matrix via brute force, performing the four dimensional integrals necessary to compute each term of the covariance (7). Eric tried this, but wasn’t happy with the computational expense, and didn’t observe an improvement compared to some other approximations when measuring velocities (but hasn’t evaluated the relative performance for characterizing line shape variations).

Perhaps the simplest approximation would be to only compute the contribution of terms that depend on the variance of the flux, but then scale up the variance by some factor. This leaves the question of what factor should be used. One can compute a minimum value based on the theoretical velocity precision which can be computed in flux space (i.e., before taking the CCF), and scale up the resulting uncertainties the ratio of the theoretical velocity precision to the velocity precision derived with the approximation of the CCF.

Another possibility would be to simply use the sample covariance matrix, but there’s the concern that won’t perform well on small datasets. A third possibility would be to use a hierarchical model for the covariance conditioned on the data. Mathematically, there’s a lot of appeal, but it’s unclear how computationally intensive it would be and it take a fair bit of work to setup. So this would probably be the last approach to try implementing.

A fourth possibility was suggested by Jinglin Zhao, computing the sample covariance of a large number CCFs generating in a bootstrap-like fashion from the actual spectra. This would still be computationally expensive, but it might be faster than the direct computation approach. Additionally, it has the advantage that it would be relatively straightforward to account for a complicated line width function (LSF), including details like how it varies across the detection.

Eric showed some CCFs, CCF minus mean CCF residuals, sample covariance of CCFs, and residuals to the rank-reduced CCF covariance model, and the mean along offset diagonals of the residuals to the rank-reduced CCF covariance model, so as to give people a sense for what the data is like.

Someone (Hogg?) asked why Eric needed to compute the covariance of the CCF in the first place. Eric replied that he was trying to use the CCF for a log likelihood that was sensitive to the line-shape changes due to stellar variability.

Eric presented the above options, hoping that someone would point out some papers where scientists had thought about this more deeply and validated one or more approximations. Unfortunately, we didn’t identify any such paper. It’s unclear what subbranch of astronomy would care about computing the covariance of the CCF accurately. Maybe there’s some other field using CCFs that would care (e.g., MRIs?).

For now, it seems that the CCF covariance approximation of 5 is state-of-the-art, at least for large datasets. If Eric manages to try the bootstrap approach, he’ll report back.

References Footnotes

- Bouchy et al. (2001)

- Boisse et al. (2010)

- Lafarga et al. (2020)

- For instruments using a gas absorption cell as a wavelength calibration, the velocity measurements are typically done using something closer to a forward modeling approach; Butler et al. (1996). The advent of optical laser frequency combs (LFCs) and etalons has enabled even more precise wavelength calibration that can leave the stellar spectrum unperturbed.

- Collier-Cameron et al. (2020)

- Dumusque et al. 2020; actually we used 910 daily average spectra from this data set, rather than all 34,550 solar spectra. The daily averages have very high SNR, ~6,000-10,000 per CCF “pixel”.

- Technically, one would need to do 6 dimensional integrals if one were to consider the finite extent of each detector pixel.

About the author:

Eric Ford has been joining in on the CCA’s Astro Data group meetings while on sabbatical, and is eager to learn from others at CCA applying advanced statistical or data science methodologies that may be relevant to detecting and characterizing exoplanets and exoplanet populations.