At this week’s meeting, I updated the group about my project with D F-M, Andy Casey (Monash University), and Tim Morton (USC- the west coast one). We are looking into how to determine how the binarity of Kepler planet hosts influence planet formation. That sounds really exciting but “determine” is doing a lot of work in that sentence. First, we have to figure out which stars are (unresolved) binaries. There are a couple of different ways in which we’ll go about doing this, but the one highlighted this week is the fruit of Andy’s work.

Alongside the astrometric and RV measurements, Gaia also lists errors associated with fits. For unresolved binaries, trying to fit the astrometric or RV curve of a single star will yield an uncharacteristically large amount of error. Through Andy’s work (which I can’t claim to understand beyond the surface level), we can turn this error into a likelihood that the star is not a single star.

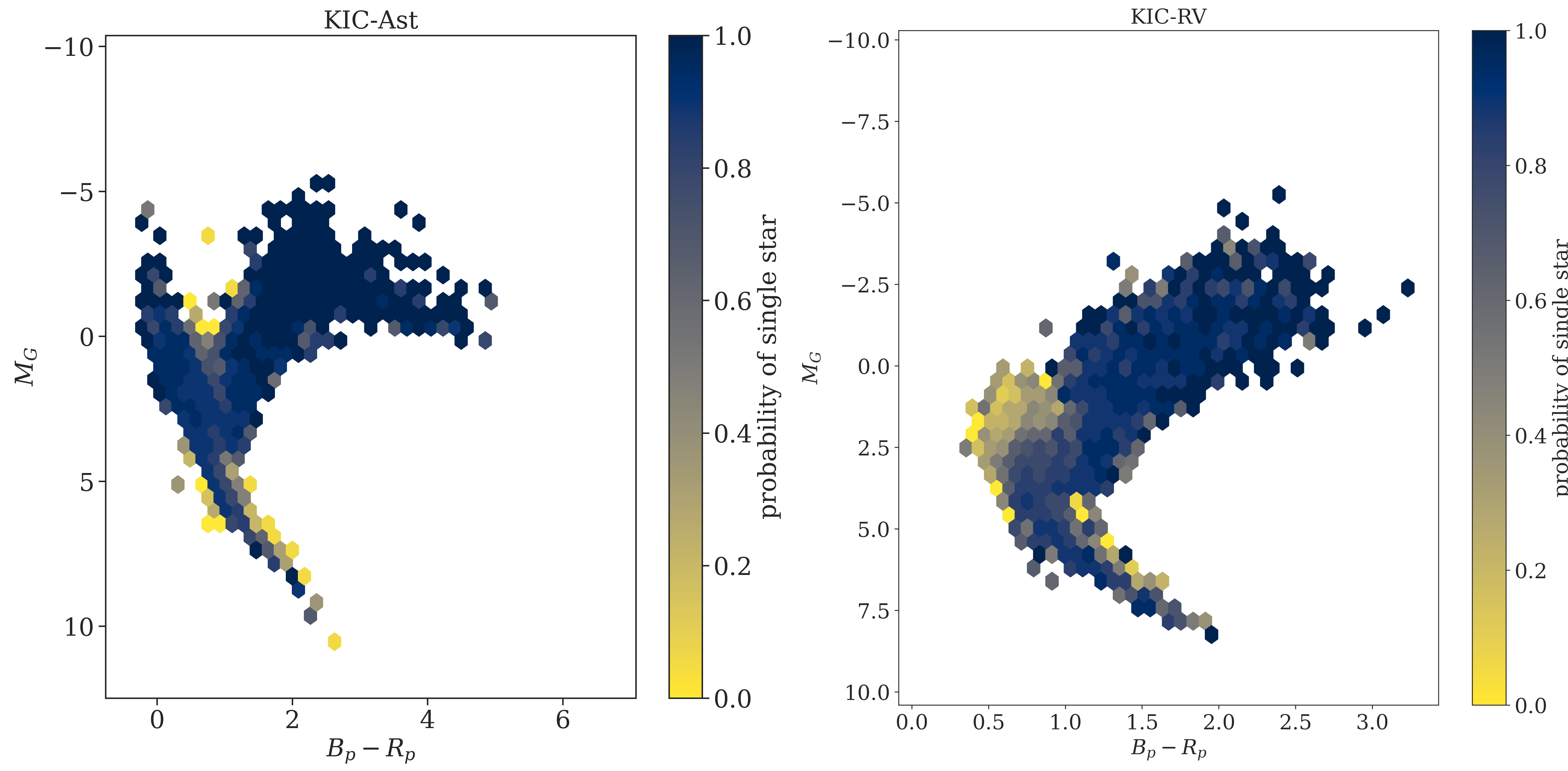

Incredibly, this seems to work really well! In the color-magnitude diagram above of the KIC stars with astrometric measurements, we can pick out the stars that have a low probability of being single above the main sequence; right where we would expect binaries to be.

Interestingly, the same plot for KIC stars with RV measurements looks very different. There are a few selection effects here we’ll have to figure out: not all stars have both astrometric and RV measurements and (as pointed out by Trevor) the population of binaries detected by astrometry is different from that of RV binaries. Known spectroscopic and eclipsing binaries are picked up through RV jitter but not astrometric jitter!

Figuring out how exactly accurate this is will be key. Because neither method is batting 1.000, exactly how to quantify “I’m pretty sure this star is not a single” represents an interesting puzzle for our near-future selves.